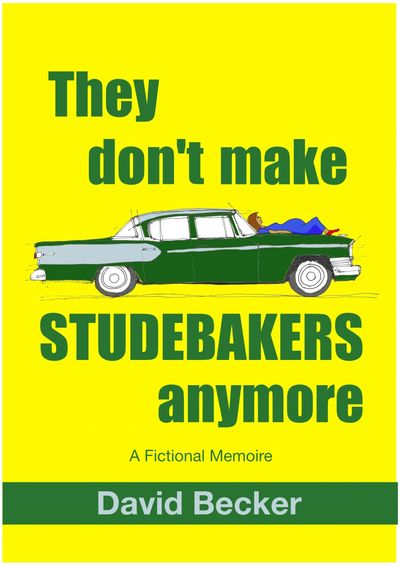

They don't make STUDEBAKERS anymore - excerpt

I was born on the hood of a Studebaker.

After what she thought was one of her last contractions, my mother assumed we weren’t going to make it to the hospital on time, so she told my father to stop the car in the shade of one of the large maple trees that lined both sides of the suburban street. Despite being late October, most of the trees still retained their leaves, so they looked like giant yellow and orange parasols reaching out to touch each other above the narrow road.

I’m told that Father watched in horror as Mother hauled herself out of the confines of the car’s interior, struggled onto the hood, hiked up her skirt, and lay on her back, warmed by the engine, her head supported by the incline of the windshield. When another contraction arrived, my mother let out a scream, punctuated by several obscenities aimed squarely at my father for having done this to her. My father was both terrified and mortified—terrified that she and I would come to some harm since he had no idea what to do, and mortified that his wife was splayed on the car, screaming swear words.

Being the late 1950s, most men dutifully trudged off to thunderous factories or nondescript offices where they apparently smoked copious numbers of cigarettes and drank a fair bit of Scotch, while most of the women stayed home to look after the house and kids. So, it wasn’t long before a woman appeared in almost every doorway up and down the block. Some were curious, some alarmed, and some annoyed that the quiet of their street had been shattered. With my father standing over a half-naked woman screaming in agony on the hood of his car, it could have looked like some sort of horrendous assault, but one or two of the women realized what was happening and came running with towels, pitchers of water, and damp cloths. One even retrieved a garden hose, to what end we can only speculate. The others simply stood and watched, some a little too close for comfort, some from the safety of their doorways, but most from a respectful distance on the adjacent front yard, where they were careful (without really being conscious of it) not to damage the golf-green-manicured lawn. Any little children who appeared in the doorways with their mothers were quickly hustled back into their houses, lest the story of the stork be revealed as the lie it was and prompted the children to raise a bunch of uncomfortable questions.

We stayed there for some time. Evidently, it wasn’t the last contraction, but my parents were afraid to get back into the car and carry on, just in case.

Finally, it happened. I arrived at 5:28 p.m. on October 4, 1957.

I sometimes think I remember being propelled through the birth canal, being gripped and gently pulled from the pressure and warmth of my mother’s body, then emerging into the dry air, suddenly feeling cold and aware of a strange brightness penetrating my onion-skin eyelids. I was suspended by my feet until I felt the sudden rush of air into my lungs and heard a wailing sound that could only have come from me. Then I was warm again, wrapped tightly but in something dry this time, and placed on the warm softness of my mother’s body.

I was told later that, once I was safely in my mother’s arms and we had been covered with a rough canvas tarp that appeared from somewhere, a doctor was called. There was no ambulance, no panic, nor even a great sense of urgency. Ambulances were reserved for emergencies. The safe arrival of a baby boy was not an emergency, regardless of where it happened. We stayed where we were, on the hood of the Studebaker, until he arrived. While we waited, several of the women came closer to look at and, I suppose, admire me. A couple of them congratulated my parents, but many of them said nothing. They just stared as if I were some kind of alien they’d never seen before, which was odd, given that most, if not all of them, would have given birth to at least one child.

My father, no longer terrified but still very uncomfortable with the whole situation, accepted the congratulations while silently chastising himself for having contributed so little. One of the other women had removed me from my mother, cleaned me up, and presented me to her. My father didn’t even cut my umbilical cord. I never found out who did that. Instead, he hovered near the driver side door of the Studebaker, ready to flee as soon as possible. When the doctor had examined my mother and me and decided we were fine, he told us to go home and rest for a couple of days. No hospital for us, apparently.

It was at home that my father’s panic really set in. He was clueless when it came to taking care of us while my mother convalesced. He knew how to heat baked beans from a can. He could fry a passable egg if you weren’t fussy about how runny the yolk was or how the thing looked. And he could make toast without burning it (most of the time); we didn’t have one of those “new-fangled pop-up toasters,” so ours required some judgment on the user’s part. But that was just about his entire repertoire. Laundry, of which there was a lot, might as well have been a mission to Mars. We were among the last people on the block to get an automatic washer, so we still had one of the old ones with the big tub and a wringer (sometimes aptly called a “mangle,” making it sound as dangerous as it was). Although it did have an electric motor, the old washing machine was just as much a mystery to him as it would have been if it had had a manual crank. With some coaching from my mother, he finally figured it out, but after a couple of attempts, some of the white clothes acquired decidedly non-white hues.

Cleaning the house simply didn’t get done.

Fortunately for both my father and me, my mother assumed responsibility for my care, so I was nourished, dressed, and changed into diapers that were pale pink, blue, green, or some combination of those colours, depending on what had been in the washing machine with them.

While my father tried to maintain a brave face, it was clear he was struggling to keep up with the demands, especially when he was exhausted because my hungry cries kept waking him in the middle of the night. So, after four days, my mother got out of bed, took over the household chores, and told my father to go out to the garage and clean the hood of the car, which he did for six hours.